William Paca and the Legacy of July 4, 1776

(remarks at the Annual Queen Anne's County July 4th Celebrations at Houghton House)

Recently David McCullough, the Pulitzer prize winning author of 1776, spoke to the 19th Annual National Speakers Conference in the Maryland State House. He fashioned his passionate plea for better education of our youth through the contemplative reading of history around two themes, “you are what you read” and the charge from Alexander Pope's Essay on Man: “Act well your part; there all the honor lies.”

William Paca's generation read widely, thought deeply, and acted with honor as they placed their lives and their fortunes on the line in the defense of an independent United States.

On July 4, 1776, William Paca had the privilege and the duty to vote for independence, along with John Rogers, a fellow delegate and distinguished lawyer, who does not get the full recognition he deserves for the courageous stand he took that day.

Samuel Chase took Roger's place in Congress in time to actually sign the Declaration of Independence on behalf of Maryland, and he, not Rogers is remembered as one of Maryland's four 'signers' memorialized with Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, and William Paca, in larger than life paintings on the walls of the current Senate Chamber in the Annapolis State House.

Indeed Samuel Chase was so unhappy that he was not present in Philadelphia to vote for independence that he fretted to John Adams about not being among those who would be remembered for his actions in support of Independence.

Neither he nor Paca needed to worry. They would be remembered, as we are remembering today, for the sacrifices they made and the wisdom they imparted in writing for future generations to reflect and act upon, if only we continue to read, think about what we read, and act well our parts wherein all the honor lies.

The touchstone of democracy is the written word. It is what legislators and constitutional conventions do to strengthen and improve our government. It is the direction that emanates from our executives. It is the interpretations that are rendered by our judiciaries.

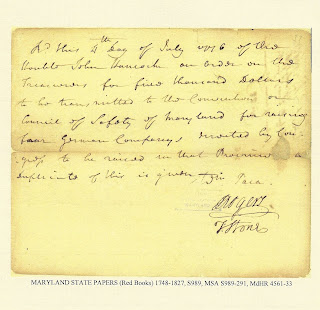

One of the first written pieces of evidence of William Paca doing his job in support of the Revolution is the note he and his fellow delegates penned the same day, July 4, 1776, that transmitted $5,000 from Congress to Maryland to assist in raising troops for Washington's army. It would be followed by a considerable body of writing, including an argument for a Bill of Rights that at first met defeat in Paca's home state, but ultimately became in part the law of the land.

In fact, despite angering George Washington by proposing that there be a bill of rights added to the Constitution, when he became president under that constitution, Washington appointed William Paca one of the first Federal Judges, a position in which he served until his death in 1799.

The importance of the written word to the governance of the free world is the unmistakable contribution of those who founded our nation. From the Mayflower Compact and the Charter of Maryland to the laws that are written in Washington, in Annapolis, and in state capitols throughout the land, we explain in writing what we expect our government to do and how we define our liberties.

It is about two such written documents that I would like to focus my remarks on today, in the context of one line of the Declaration of Independence which reads:

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

The 'he' was King George, and the concern was that for a republic to survive, it must have free and convenient access to the written records of government. In today's world that means more than what we put on paper. It means the electronic record as well, which is far easier to abuse and lose than paper.

Just recently the Archivist of the United States sent out a letter to an unknown number of American citizens warning them that a hard disk from the White House had been lost containing personal information from an unknown number of citizens including our current governor. The National Archives offered to monitor their credit ratings and assist in rectifying any abuse of the information, but it should not have been lost in the first place. Anyone who has lost his or her identity to cyber thieves knows how fatiguing it is to recover that identity. Not only must the depository of the public records be accessible to the public, it also needs to be reliable, accountable, and protected from abuse by kings and citizens alike.

The two documents I would like to bring to your attention today and hope that you will take time to read with care are fundamental to understanding the nature of our republic. One was penned by George Washington, the other in part by William Paca.

The import of the first, given in the Maryland Statehouse on December 23, 1783, would be debated to the present, as would the outcome of the propositions William Paca made in April 1788, when Maryland's ratification convention gave its assent to the draft Constitution of the United States.

The first is one of the most important documents in American History to remain in private hands until the 21st Century. It is George Washington's draft and reading copy of his remarks on resigning his commission as commander in chief, on December 23, 1783, a speech that took place in the Old Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House, then being used by Congress when Annapolis was the Capital of the United States.

In the most dramatic of ceremonies, Washington bowed to civil authority, charging Congress with governing the new Nation and making it clear that one of their chief obligations was to reward and care for his officers and men who had fought so hard to bring them independence. It was a charge and a responsibility that is still with us today. Presidents are the Commanders in Chief, and they often face the responsibility of that office directly, as President Truman did with General MacArthur and President Obama did with General McCrystal. President Lincoln even quoted Alexander Pope in an exasperated letter to a General during the Civil war (Tarbell IV, p. 222). As commander in chief he wrote General Hunter:

I have been, and am sincerely your friend; and if , as such, I dare to make a suggestion, I would say your are adopting the best way to ruin yourself. “Act well your part, there all the honor lies.” He who does something at the head of one Regiment, will eclipse him who does nothing at the head of a hundred”

a belief that President Lincoln carried forward in his dealings with other Generals including George McClellan.

Congress has been slower to react to its responsibilities in the current conflicts facing us, but in the past has done much to aid the veteran, such as the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, P.L. 78-346, 58 Stat. 284m) better known as the GI Bill that helped returning service men and women to college where they were able to become what they read and continue to act well their parts wherein all the honor lies.

William Paca was present at the delivery of Washington's farewell address that December 23, 1783, in the Old Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House. He was just beginning his second term as Governor, having been re-elected on November 22, 1783, the anniversary of the departure of the first settlers to Maryland 150 years before. He was at the head of the delegation that welcomed Washington to Annapolis, and after Washington's speech, accompanied him as far as the ferry at South River, on Washington's return journey to Mount Vernon that afternoon.

With the considerable help of private citizens Willard Hackerman and Henry Rosenberg, the Maryland State Archives acquired Washington's draft of his speech, a copy of which is in your handout today. With continuing donations from the private sector, we hope to place it on permanent display in the room where it was given.

What is so important about a draft of a speech in George Washington's hand? It is by far the most important piece of evidence in the history of what writer Stanley Weintraub has described as George Washington's Christmas Farewell, a journey from New York to Annapolis where he intended to achieve "the seemingly impossible feat of backing away from dictatorship while keeping the newly freed Americans together as a nation." [p. 13]

It is that priceless link on paper to the mind of the man who believed that civilian government and leadership was the only answer to the future of the Republic.

On the evening of Friday, December 19, 1783, Washington rode into Annapolis with two aides, David Humphreys and Benjamin Walker, Philip Walmsley, a servant, and a large honor guard of comprised of "Generals Gates and Smallwood, and several of the principal inhabitants of Annapolis." They proceeded to George Mann's Tavern, the confiscated residence of a Loyalist with whom Washington had often dined before the war, and where "apartments had been prepared for his reception."

Flying from the State House was the largest American flag yet made, a replica of which is now on exhibit, suspended from inside the dome of the State House. The town and those congressmen who managed to make their appearance warmly greeted the general. Given the number of receptions culminating in a Ball at the State House, it is a wonder that Washington had time to write anything. Yet on his arrival he did not know if Congress expected him to speak or merely show up and surrender his commission. On Saturday the 20th he wrote Congress inquiring as to what they had in mind. Congress formed a geographically balanced protocol committee composed of Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, the Author of the Declaration of Independence and soon to be minister to France, Dr. James McHenry of Maryland, formerly aide and physician to General Washington, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts (probably best known in political history for his later efforts as the author of Gerrymandering). They immediately responded through the President of Congress, Washington's old adversary, Thomas Mifflin from Pennsylvania, that indeed he was expected to make a speech the following Tuesday, December 23rd, in a ceremony that was carefully designed to emphasize the sovereignty of civil authority as then vested solely in Congress.

From Saturday, December 20, until slightly after noon on Tuesday, December 23, 1783, Washington was exceptionally busy. The following Thursday, Christmas Day, the Maryland Gazette would fill one whole page with an account of the receptions, dinners, balls, and addresses from the Governor and Council, the General Assembly, the Mayor, Recorder, Alderman, and Common-Council of the City of Annapolis. To each official body Washington made a formal and written reply, while also dining and toasting at a prodigious rate. As the Gazette reported, for example, on Monday afternoon, the night before his speech in the State House, "Congress gave his Excellency a public dinner at the Ball-room, where upwards of two hundred persons of distinction were present; every thing being provided by Mr. Mann in the most elegant and profuse stile." After dinner [thirteen toasts] were given including number 10, "May Virtue and wisdom influence the councils of the United States, and may their conduct merit the blessings of Peace and Independence."

That same night "the stadt-house was beautifully illuminated, where a Ball was given by the General Assembly, at which a very numerous and brilliant appearance of ladies were present." According to Congressman James Tilton writing on Christmas Day, 1783, "The General danced every set, that all the ladies might have the pleasure of dancing with him, or as it has since been handsomely expressed, get a touch of him."

December 23rd at noon was set for the formal ceremony of resignation. Washington took great care in reworking his draft for delivery, assigning his aide Benjamin Walker the task of making an initialed copy for the Congressional record. It is clear from what Washington crossed out that he had two goals in mind in making this speech, one of the most important of his whole career: reinforcing the supremacy of the civil authority and leaving the door open for his being called back to civilian service. The changes in the final draft, overlooked by scholars who cite the official recorded versions at the National Archives and the Library of Congress, are significant.

Washington added congratulations to Congress, pointed to the opportunity the United States had of becoming a respectable nation, crossed out FINAL from before farewell, and ULTIMATE before "leave of all the enjoyments of public life." He would be willing to serve again if asked, but especially in any effort designed to strengthen the Civil Authority of the Republic.

In that regard the Maryland General Assembly's address of Monday, December 22, 1783, signed by Senate President Daniel Carroll and House Speaker Thomas Cockey Dye, proved prophetic.

We are convinced [wrote the Maryland General Assembly] that public liberty cannot be long preserved, but by wisdom, integrity, and strict adherence to public justice and public engagements. This justice and these engagements, as far as the influence and example of one state can extend, we are determined to promote and fulfill; and if the powers given to Congress by the confederation should be found to be incompetent [meaning inadequate] to the purposes of the union, we doubt not our constituents will readily consent to enlarge them.

In three and half years Washington would return to National public service at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. He explains his commitment to strengthening the civil authority in his written response to the Maryland General Assembly which he composed and delivered that same day, December 22, 1783:

You have rightly judged, Gentlemen, that public liberty cannot be long preserved, without the influence of those public virtues, which you have enumerated. May the example you have exhibited, and the disposition you have manifested, prevail extensively, and have the most salutary operation! For I am well assured, it is only by a general adoption of wise and equitable measures, that I can derive any personal satisfaction, or the public any permanent advantages, from the successful issue of the contest. I am deeply penetrated with the liberal sentiments and wishes contained in your last address to me as a public character, and while I am bidding you a final farewell in that capacity, be assured, Gentlemen, that it will be my study in retirement not to forfeit the favorable opinion of my fellow-citizens.

Washington left the door open to a return to public service and I suspect that night or the next morning, crossed out 'final' from his formal farewell to Congress. Five years later he would be President and the first civilian Command-in-Chief.

Among the special collections of the Maryland State Archives, we have a letter written by one of the women who was present. From one of the fine Colonial mansions still standing in Annapolis Molly Ridout wrote to her mother in London:

My Dear Mamma:

I went with several others to see Genl Washington resign his commission. The Congress were assembled in the State House. Both Houses of Assembly were present as spectators. The Gallery [was] full of Ladies. The general seemed so much affected that everybody felt for him. He addressed Congress in a short speech but very affecting. Many tears were shed.... I think the world never produced a greater man & very few so good.

Included with the more recent acquisition of the final draft of Washington's speech, is another contemporary account written by State Senator and Congressman James McHenry to his bride to be in Philadelphia, Peggy Caldwell. It is a letter written over several days, including December 23, 1783, during which McHenry was a member of the Congressional protocol committee and a participant in the ceremonies.

The ceremonies began at twelve noon on December 23 rd. According to the protocol developed by Thomas Jefferson and his committee, Congress met and took their seats, leaving their hats on as a sign that until Washington was a civilian they would not display any deference or sign of subservience. General Washington entered the chamber and was escorted to a chair near the President of Congress. There he waited until the galleries were filled and the President called for silence. He then rose, bowed to Congress, who remained seated with their hats on and did not bow, and delivered his remarks. James McHenry, more than any other observer, captured the drama of the moment in his letter to Peggy Caldwell:

Today my love the General at public audience made a deposit of his commission.... It was a solemn and affecting spectacle; such [a] one as history does not present. The spectators all wept, and there was hardly a member of Congress who did not drop tears. The General's hand which held the address shook as he read it. When he spoke of the officers who had composed his family, and recommended those who had continued in it to the present moment to the favorable notice of Congress he was obliged to support the paper with both hands__But when he commended the interests of his dearest country to almighty god, and those who had the superintendence of them to his holy keeping, his voice faultered and sunk, and the whole house felt his agitations. After a pause which was necessary for him to recover himself, he proceeded to say in the most penetrating manner. —"Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, and bidding an affectionate farewell to this agust body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission and take my leave of all the employments of public life"—So saying he drew out from his bosom his commission and delivered it up to the president of Congress...

This is only a sketch of the scene [McHenry continued] But, were I to write you a long letter I could not convey to you the whole. ...the past - the present - the future- the manner—the occasion all conspired to render it a spectacle inexpressively solemn and affecting. But I have written enough. Good night my love, my amicable friend good night.

Once the President of Congress replied to his speech, Washington bowed again to Congress, who then removed their hats in an orchestrated gesture of respect, and he retired to the Committee Room next door to the Senate Chamber.

After a little time, while the spectators withdrew, Washington stepped back into the room, bid every member of Congress farewell, and then rode off from the door of the State House with Governor Paca at his side, intent upon eating his Christmas dinner at home at Mount Vernon. Governor Paca accompanied him as far as the South River Ferry. Washington paused long enough at Londontown for a meal with his servant, Philip Walmsley, and then continued on his way, via the Patuxent Ferry to over night accommodations at Queen Anne, Prince George's County, having recorded an expenditure of $50 his own money at the festivities in Annapolis.

Washington devoted the remainder his life to furthering the prosperity of the new nation, fearlessly stepping back into the arena of civil government when he thought he could contribute to its improvement. It is that generosity of public spirit, that devotion to "We the People, in order to form a more perfect union," which this document underscores, and which makes it such an important link in the written record of our longevity and achievement as a Republic.

William Paca, too, devoted the rest of his life to reading, writing and acting on what he read and wrote. His personal life was full of tragedy and ambiguity, especially on the matter of slavery, but his public life was one of honor, thoughtful reading, action, and constructive advice to his and future generations.

In reflecting on William Paca's contributions to the public world and the future of the nation, we not only pay homage to his times, but also to that of Arthur Amory Houghton, Jr. who, through his generosity, ensured that we would not forget William Paca. In part, Mr. Houghton's legacy surrounds us here today, but we also find it in the mystery of the earliest known manuscript in English of the Maryland Charter that he gave to the Maryland State Archives and in the on-going research he stimulated with the biography of Paca which he conceived and underwrote. And, finally, we find his legacy in the serenity of the courthouse square in Centreville where his gift of the statue of Queen Anne sits below the spot where an ever vigilant American eagle once reigned before being removed for conservation and restoration.

You might ask how a 17th century copy of the Maryland Charter could have anything to do with William Paca, a native of Harford County who was born in 1740 and who died at his estate on Wye Island in Queen Anne's County in 1799. The answer lies in the importance of that document to all that William Paca stood for in his political life. The Charter was the basis of representative government in Maryland, specifying that the laws of the province had to be "of and with the advise, assent, and approbation of the free-men of the said Province, or the greater part of them, or of their delegates or deputies." It provided the grounds upon which Paca, as one of the leading lawyers of the day, developed his belief that fundamental rights needed to be written down and explained to ensure that each successive generation would benefit from them.

In late April and early May of 1788, Paca acted on those principles and submitted a series of propositions, many of which ultimately were incorporated into the first 10 amendments of the U.S. Constitution. Indeed, his 22 draft amendments to the Constitution and those of his pro-amendment colleagues form the first fully articulated and detailed printed agenda for a bill of rights and deserves much more attention than scholars have hitherto credited it.

Lost until 1984, when the manuscript was purchased by the state Archives, the amendments to the Constitution Paca proposed in 1788, begin with a ringing declaration drawn from the Maryland Declaration of Rights which Paca also helped draft in 1776 as part of Maryland's first State Constitution. This language is still embedded in Maryland's Constitution but was never carried to the federal level:

That it be declared, That all persons intrusted with the legislative or Executive powers of Government are the Trustees and Servants of the Public and as such accountable for their Conduct. Wherefore whenever the Ends of Government are perverted and public Liberty manifestly endangered and all other means of Redress are ineffectual the People may, and of right ought object to, [or] reform the old, or establish a new Government, the Doctrine of Non Resistance against arbitrary power and Oppression is absurd Slavish and destructive of the Good and Happiness of Mankind.

Paca's amendments include the provision

(11) "that there be no national Religion established by Law but that all Persons be equally entitled to protection in their Religious Liberty" and conclude with requirements for freedom of speech and

(21) that "Congress shall exercise no power but that what is expressly delegated by this Constitution."Today I will leave you to contemplate the printed version of the debate that ensued in the Maryland Statehouse that long ago spring of 1788. What you have before you is a copy of the rare printed broadside that was sent to the Virginia Ratifying Convention, where it shaped the thinking and the resulting propositions for a Bill of Rights that James Madison would shepherd through to enactment by the First Congress of the United States.

As David McCullough so eloquently put it before the leadership of all the lower houses of the United States assembled in the House of Delegates Chamber of our State House the evening of June 16, 2010:

You are what you read, and that when you act as citizens or public servants, “Act well your part; there all the honor lies.”

My only caution is that, if you do not set aside the resources to save what is written, on paper or electronically, in a permanent public archives, what you are able to read of the present will be little of value to the future, and acting your part, no matter how honorable, will be without direction or substance.