If you have found our on line and in person services at http://mdarchives.net of use and important to you, you can make a donation in any amount on line to the Friends of the Maryland State Archives: https://shop1.mdsa.net/Donation/donate.cfm

You can also be vocal by writing directly to the governor, the comptroller and to the Maryland legislature, including the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate. You will find their email addresses on our http://mdelect.net web site. If you are a Maryland resident, you can also determine who represents you in the legislature by your address.

The principal responsibility and legally mandated mission of the Maryland State Archives is to be the safe, reliable, and accountable repository of the State's public memory, accessible to all at as little cost for access as possible. It should be at the Archives where you can reflect on and build upon the lessons learned about what ought to be government's role in protecting the lives and livelihoods of it citizens, and to sharpen our personal understanding of our origins and obligations, both as citizens and as family members in search of our roots. As President Lincoln wisely pointed out, we need to reach to those the mystic chords of memory that touch the better angels of our nature. Those who remain ignorant of their past, be it personal or public, will wander lost through life, susceptible to the mob rule of others as ignorant and self-destructive as they are to themselves. Yet if we do not now provide the professional care and archival storage for our public memory we will be left with only candlesticks and no candles to light our way.

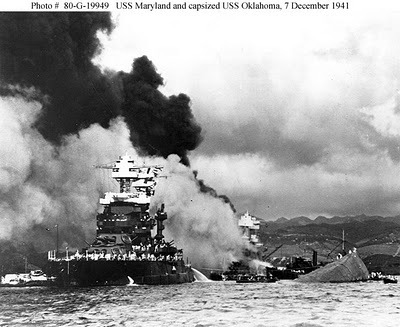

We can and do find some resources to restore some artifacts, such as this restored Garrett County sponsored candlestick from the State's Artistic property inventory. It, which along with the rest of the silver that the citizens of Maryland including countless school children with their pennies, purchased, was given to the Cruiser Maryland in a gala ceremony at the Annapolis dock in 1906. Money can always be found to polish silver, but apparently not to hold on to the memories of those who lovingly bought it, and gave it for the use of the officers and crew of first the Cruiser and then the Battleship Maryland. My favorite photograph of the U. S. S. Maryland, is of her, injured, but steaming forth out of the chaos of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 to do her duty.

Photo #: 80-G-19949 Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941

USS Maryland (BB-46) alongside the capsized USS Oklahoma (BB-37).

USS West Virginia (BB-48) is burning in the background.

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives collection

In many ways as State Archivist, in charge of keeping the public memory, I feel like a member of the crew on that valiant ship on that fateful day, not knowing how we will navigate our way out of the troubles we are in, but certain that we must and we can.

Records and Artifact Storage. While the Maryland State Archives has suitable storage capacity for paper records totaling 168,680 cubic feet, in its custody are 359,633 cubic feet of record material. Of these, some 190,963 cubic feet are stored in spaces ill-suited and even detrimental to their long-term preservation. Indeed, problems relating to records management in general and the Archives in particular have only gotten worse with time. The same is true for our extensive art collection which is ill housed and for which we have limited special fund resources for restoration of only a few of the treasures in our charge.

Since 2005, when the Archives first requested a capital allowance for records storage, the amount of space suitable to house permanent records has remained the same. The Archives’ main facility in Annapolis – the only suitable facility available – was filled to capacity (168,680 cubic feet) in the year 2000. Since that time, the Archives has taken on an additional 190,953 cubic feet of records. Thus, nearly 200,000 cubic feet of records - - well over half of the State’s total permanent holdings - - are housed in rented facilities that are totally unsuitable.

For the long-term preservation of record material and fine art, environmental control is vitally important. The impact of temperature, relative humidity, air quality/pollution, and light has been studied and recognized the world over. The lack of temperature and humidity controls at the adjunct warehouses of the Archives, without question, puts record material at risk. The consequence of inaction is the degradation and ultimate destruction of Maryland records and fine art.

Staffing and Succession Planning. Like many state agencies. The Archives has had difficulty over the years in retaining qualified staff. It has become quite routine for IT staff and junior archivists to get their training at the Archives and then move on to higher paying jobs. We know we will never be able to compete with the salaries of the federal government or that of the private sector, but our problem is seriously exacerbated by the fact that most of our junior professional staff do not have “PIN” positions with benefits. The real dilemma this portends for the future will be compounded by the fact that there are many of our senior staff who are now, or will be soon, eligible for retirement. Without trained, experienced junior staff to replace them, the Archives as an institution is in peril, not unlike the U.S.S. Maryland at Pearl Harbor.

At our last budget hearing, the budget analyst asked that we address what we can do to rectify the critical storage problems we face right now. I have no easy answer. We have maxed out our ability to raise special funds. So much of what we have been able to earn through our entrepreneurial on line services has already been sucked away to pay for substandard warehouse rent. The short response is that in the short run we must have a direct appropriation for rent of a storage facility that meets minimal archival standards just to accommodate the permanent records that are sitting in expensive agency office space or are being thrust upon us because of the downsizing of government. Where will that come from? It is not allocated in this budget before you and I know of no private angel of mercy who will fund it for us, even though I have indeed tried to find one. The last time I tried unsuccessfully, Bernie Madoff had a great deal to do with why I was turned down. Perhaps by taking but a small amount from every other priority that is funded throughout the budget, a reallocation to us for temporary archival storage can be achieved while we await better times and a capital appropriation?

While we also realize that we must do more with less, we can't do anything if we do not have a core professional staff to manage our collections and to seek out new sources of special fund revenue, while maintaining the flow of what we already have which currently amounts to about 80% of what it cost to maintain our current inadequate level of storage and service.

This is not to say that we have not re-thought our staffing goals and reduced them significantly through the creative use of volunteers and utilization of what is called a 'cloud' approach to storing, indexing and accessing our records. What I mean by a 'cloud' is a techy term related to sharing resources privately and publicly owned. For example, our pioneering efforts to share electronic storage with a consortium of Libraries and State Archives, because of the leadership role we have played in creating a true electronic archives, should result in significant on-going support from the rest of partners for storing their collections in our electronic archives facilities.

Just recently the Library of Congress interviewed me as a digital pioneer, the pod cast of which was to be released on Valentine's Day. While I am flattered, what that means is that Maryland has been recognized by those in the business of preserving and making accessible electronic information as a leader in coming to grips with the storage and retrieval of permanent electronic records. Our on-line access to all the land records ever recorded in Maryland (at least those that survived court house fires) has no peer and is looked upon as a model electronic archival system. I fervently hope that what we have accomplished is not undermined by our inability also to properly care for the permanent paper records and artifacts poorly stored or awaiting transfer.

Despite the worrisome outlook for the proper care and management of our paper and artifact holdings, we do continue to deliver a very high level of service to the public and public agencies. Just a glance at the statistics of service accompanying our budget each year proves that point.

We also have an active Friends group that in small but meaningful ways assists us in salvaging records for public use that would otherwise be lost, and with helping us properly interpret the treasures in our collections. To date they have raised about half the funds necessary to exhibit Washington's draft of his speech that he gave in the Old Senate Chamber on December 23, 1783, establish firmly the principal of the primacy of the Civil Authority in our Republic. I was proud to be able to display that speech to Mrs. Obama and members of the Obama family last summer. Now all we need is to complete the work of the capital appropriation to restore the Chamber that the President of the Senate successfully sponsored last session.

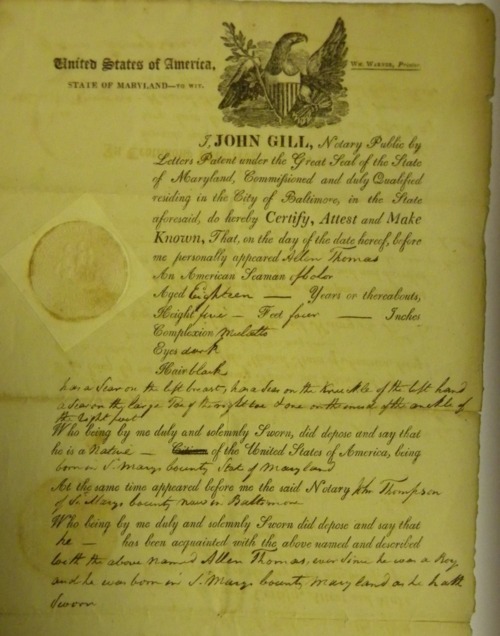

A year ago the Friends of the Maryland State Archives came to the rescue of a fine private collection of records relating the history of Baltimore City, including this rare original Seaman's certificate which documents the beginning of the sailing career of a St. Mary's county mulatto by the name of Allen Thomas. Note the poignancy of what the document makes clear. He was 'free' but definitely not a citizen. That would take a civil war and for successive generations of his brethren, decades of struggle in and out of the courts for civil rights, a public record that we cannot afford to lose, yet is in danger if we don't store it well.

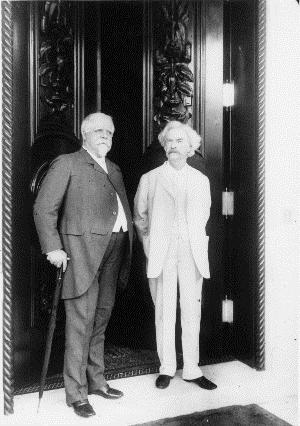

Mark Twain with Governor Warfield at Government House, May 1907

I suspect that by now you may be wondering where Mark Twain fits into all this discussion of preserving the public memory.

A year after the school children of Maryland labored to help pay for the Battleship Maryland Silver Service (which we will soon have on display again in the State House thanks to the generosity of the Senate and private donors) Mark Twain came to Annapolis, straight from his bed where he had been dictating his autobiography to his secretary Miss Lyon (Mrs. Twain was long dead but fondly remembered).

Twain's visit and the humor he dispensed on the occasion was widely reported in the newspapers of the day from Maine to Texas and beyond.

Twain came to raise money for the First Lady's favorite cause, her Presbyterian Church in Annapolis, which needed a new roof. The desire to hear from Twain was so great that his after dinner speech was moved from the Governor's Mansion to the recently dedicated, new House of Delegates Chamber, the one still in use today. He regaled the crowd with story after story. Peals of laughter filled the chamber as he told of the day he drowned, the watermelon he stole, and the tale of the drunken sailor who at the end of the story was heard through the darkness explaining to his wife “with a fervent, appropriate, and pious ejaculation. “God help the poor sailors out at sea.”.”

As was nearly always with Mark Twain, under the humor lay a serious message. It was a message of the importance of memory; remembering the good and evil that has befallen us, with humor yes, but as lessons not to be forgotten.

Take his memory of his life near Hannibal Missouri on the farm of his Uncle, John Quarles. And what he learned about slavery.

There was … one small incident of my boyhood days which touched this matter [of slavery] and it must have meant a good deal to me or it would not have stayed in my memory, clear and sharp, vivid and shadowless, all these slow-drifting years. We had a little slave boy whom we had haired from some one there in Hannibal. He was from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, and had been brought away from his family and his friends, half way across the American continent, and sold. He was a cheery spirit, innocent and gentle, and the noisiest creature that ever was, perhaps. All day long he was singing, whistling, yelling, whooping laughing –it was maddening, devastating, unendurable. At last one day, I lost my temper, and went raging to my mother, and said Sandy had been singing for an hour without a single break, and I couldn't stand it, and wouldn't she please shut him up. The tears came into her eyes, and her lip trembled, and she said something like this--

“Poor thing, when he sings, it shows that he is not remembering, and that comforts me; but when he is still, I am afraid he is thinking, and I cannot bear it. He will never see his mother again; if he can sing, I must not hinder it, but be thankful for it. If you were older, you would understand me; then that friendless child's noise would make you glad.”

It was a simple speech, and made up of small words, but it went home, and Sandy's noise was not a trouble to me any more.

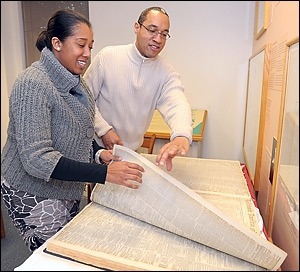

One bit of good news that I am pleased to share is that because of our efforts to document the history of slavery in Maryland, The U. S. Department of Education has awarded us us a grant of $739,000 over three years to continue our research on the this history slavery on Maryland's Eastern Shore. That in essence means that we can continue to have a nationally recognized research program without any significant drain on the general fund. (See: The Capitol, for 2/3/2010, http://www.hometownannapolis.com/news/top/2011/02/03-26/State-archivists-uncover-stories-of-slavery.html).

Paul W. Gillespe — The Capital: Chris Haley, director of the Study of the Legacy of Slavery in Maryland at the Maryland State Archives, and research archivist Maya Davis look over 150-year-old copies of the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser, where the news item about Harriet Tubman was discovered.

As to Mark Twain, he left Annapolis earlier than planned for his bed at home in New York, and further dictation to Miss Lyon of his autobiography, the complete edition of which he insisted could only be published 100 years after his death, largely because of the truthful things he said about a lot of people. So far only the first volume has been published, making it in 735 pages to dictation in 1906. I can hardly wait to read what he had to say about his Annapolis sojourn and Mrs. Warfield's benefit in 1907, but at least the prospects of doing so are near at hand. He saw to the recording and preservation of his memories. We must do the same with our public memory. We must find the resources to preserve, protect, and to access those memories to maintain our sense of mission, accomplishment, and humor in public affairs. I can but give what I believe is good advice and advocate for what I believe ought to be done as the Custodian of the State's public memory. I and the staff can only be as successful if the literally hundreds of thousands of people who use our on-line resources take to the virtual streets through tweets, blogs, and email to convince our executive and legislative leaders that it is imperative that they help us find the resources to meet the archival challenge of preserving and making freely accessible the collective memory of the past.

A generation which ignores history has no past and no future.

Robert Heinlein, The Notebooks of Lazurus Long

US science fiction author (1907 - 1988)

"The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature." Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address.